from Yunte Huang, The Poetics of Error

Written on the walls of the wooden barracks of the detaining station on Angel Island off the coast of San Francisco, Angel Island poems delineate historical trajectories that are in many ways unaccountable in canonical discourses. They belie the pitfalls of teleological History by virtue of their modes of inscription. … I want to look at these poems as examples of tibishi (poetry on the wall), a traditional Chinese form of travel writing that provides an outlet for the large social sector which is denied the right to write history. Seen by its cultural function, tibishi in the case of Angel Island poetry becomes indistinguishable from graffiti, a scriptural practice that is sometimes condemned as vandalism and at other times commissioned as artwork. Not understanding the scriptural economy of these poems has led to a reductive hermeneutics in the hitherto efforts of transcribing, translating, and interpreting them. This kind of hermeneutics may sit well with an economic system that favors productive abstraction and with a political system that recognizes only fully-fledged citizen-subjects, but it lies at odds with what I call the poetics of error. Characterized by misspellings, misattributions, and mistranslations, the poetics of error in these poems has significant linguistic, historical, and cross-cultural implications. Read differently … misspellings spell out linguistic nonconformity and the fictionality of standard orthography, misattributions can be attributed to folk revisions of authorized history and intentional conflations of cultural origins, and mistranslations translate code-switching and heteroglossia. Understood this way, the poetics of error echoes the liminality as well as subversity of the anonymous poets' status in a world delineated by expansionist or nationalist historiography.

[A sampling of poems follows.]

Over a hundred poems are on the walls.

Looking at them, they are all pining at the delayed progress.

.

There are tens of thousands of poems composed on these walls.

They are all cries of complaint and sadness.

.

Let this be an expression of the torment which fills my belly.

Leave this as a memento to encourage fellow souls.

.

My fellow villagers seeing this should take heed and remember,

I write my wild words to let those after me know.

.

The sea-scape resembles lichen twisting and turning for a thousand li.

There is no shore to land and it is difficult to walk.

With a gentle breeze I arrived at the city thinking all would be so.

At ease, how was one to know he was to live in a wooden building?

.

The insects chirp outside the four walls.

The inmates often sigh.

Thinking of affairs back home,

Unconscious tears wet my lapel.

.

In January I started to leave for Mexico.

Passage reservations delayed me until mid-autumn.

I had wholeheartedly counted on a quick landing at the city,

But the year's almost ending and I am still here in this building.

.

A building does not have to be tall;

if it has windows, it will be bright.

Island is not far, Angel Island.

Alas, this wooden building disrupts my travelling schedule.

Paint on the four walls are green,

And green is the grass which surrounds.

It is noisy because of the many country folk,

And there are watchmen guarding during the night.

To exert influence, one can use a square-holed elder brother.

There are children who disturb the ears,

But there are no incoherent sounds that cause fatigue.

I gaze to the south at the hospital,

And look to the west at the army camp.

This author says, "What happiness is there in this?"

.

Being idle in the wooden building, I opened a window.

The morning breeze and bright moon lingered together.

I reminisce the native village far away, cut off by clouds and mountains.

On the little island the wailing of cold, wild geese can be faintly heard.

The hero who has lost his way can talk meaninglessly of the sword.

The poet at the end of the road can only ascend a tower.

One should know that when the country is weak, the people's spirit dies.

Why else do we come to this place to be imprisoned?

.

Leaving behind my writing brush and removing my sword, I came to America.

Who was to know two streams of tears would flow upon arriving here?

If there comes a day when I will have attained my ambition and become successful,

I will certainly behead the barbarians and spare not a single blade of grass.

[Poems relate to the anthology Island: Poetry and History of Chinese Immigrants on Angel Island 1910-1940, edited & translated by Him Mark Lai, Genny Lim, & Judy Yung, University of Washington Press, 1980, 1991. The full version of Yunte Huang’s essay can be found at http://ubu.com/ethno/discourses/huang.pdf & more in his book, Transpacific Imaginations (Harvard University Press, 2008) .]

I. Prologue

Years ago now

I spent a morning in a small park

at the center of Beijing Normal University.

Hunched over in benches,

or pacing back and forth,

students are reading English aloud from textbooks.

I can’t recall what anyone was saying;

I had not attended to the frequency of meaning,

but to the frequencies of sound—

the strange opening of Chinese vibrations

beneath the surface of each English word.

They spoke Chinese syllables

rearranged into English syntax and diction;

and Chinese made a home in English,

had become English

without having stopped being Chinese.

Turn you head slightly to the left,

and you hear English,

slightly to the right,

Chinese,

straight ahead, neither,

both.

We were all foreigners here.

In this fusion of Chinese and English

we all have a choice to make.

We can pull back the curtain of sound

to peek through the windows

or just rest a while in our dark rooms.

For years I immersed myself

in this Yíngēlìshī

and its chanted songs, its beautiful poetry

have changed everything

I thought I knew about our languages

II. Introducing Yíngēlìshī

I call this fusion of my two languages, Sinophonic English, or, Yíngēlìshī 吟歌丽诗 (spelled in Sinophonic English). I have chosen these characters to oppose popular ideas of “Chinglish” as “bad English.” Instead, I want to bring awareness to its eerie poetic beauty, its haunting music, and to the absolutely singular poetry it is capable of generating. Of course, “Sinophonic English” is not particular to the students in the park, but is fast becoming a dominant global dialect of English. A fusion of the two primary languages of globalization: Chinese and English, variations of this Sinophonic English is being spoken by more people than there are Americans alive (over 350 million), and has already begun to transform the language of the global marketplace. English purists everywhere will no doubt begin to clamor toward “rescuing” English from this Sinophonic dialect, but I am more interested in experimenting with this new global language. Since 1997 I have been experimenting with this linguistic fusion and working toward a transpacific imagination where a Chinese-English poetry, poetics, philosophy, and ethics might be born in a language that belongs to both Chinese and English speakers, and yet neither as well. But in the end, I have simply fallen in love with both the poetry generated between these languages and the translingual voices that emanate from them.

To bring this dream of Yíngēlìshī 吟歌丽诗 into the world, I have rewritten a large portion of a totally ordinary English phrasebook that you can pick up in most any Chinese bookstore, which teaches English through transliteration. In a sense, this book is not unlike Duchamp’s “urinal” insofar as both are “found art.” But I have totally rewritten this book by changing all the original’s simple Chinese characters (chosen to “pronounce” common English phrases) into complex Chinese poetic phrases and “poems.” I have recomposed the Chinese in mixture of modern and Classical characters to suggest passages resonating with Confucian meanings like the Sinophonic fusion of the characters 孤 德 貌 宁 gū dé mào níng which can be translated as “Even alone, the Moral one appears peaceful” but is heard by the English speaker as “Good Morning.” So the Sinophonic poems that make up the first half of this book exist as short Chinese character stanzas, but like the phrase book, they are sandwiched within Chinese and English to reveal to all readers what is taking place both aurally and semantically in the poem. Take for example this more Buddhist leaning stanza:

请原谅我

Please Forgive me

pǔ lì sī , fó gěi fú mí

普利私,

佛给浮谜

vast private profits,

Buddha offers impermanent mysteries

Here only the line “普利私,佛给浮谜” is truly Sinophonic English poetry, but the other lines are there to let both Chinese and English readers know what the line means in both Chinese and English.

So on one level this is a book of experimental Chinese poetry that blends classical allusions and contemporary vernacular to be read as “stand-alone” Chinese poems, yet to the English speaker, the very same characters resonate accented English phrases that tell the story of a Chinese speaker who uses his/her limited English to negotiate the trials of traveling to and becoming lost in America. For as it turns out, the phrases of this handbook end up constructing a narrative, a tragedy in fact since the “protagonist” is robbed soon after arriving in America and is left alone in an alien language and land with no friends, no money, no passport and no way to understand the English language which appears to have swallowed her/him whole. When I first read this simple phrase book, I felt so moved, not because of its melodramatic tenor that capitalizes on the commonly exaggerated danger of traveling abroad, but because of the accented voice that never really becomes English because it never really stops being Chinese. If the vulnerable voice of the protagonist is the tragic “chanted song” of this book, then the poems that take shape within the phonetic architecture of this simple story are its beautiful poetry.

What emerges on the pages

is a figment of a transpacific imagination,

a dimly remembered dream of translingual consciousness

born in the strange half-light of cross-linguistic procreation.

Regardless of whether you are an English Speaker

a Chinese speaker (or both),

it is my hope that you will wake up

from this dream of reading

with the dim memory of having spoken in another’s language.

III. “Evolving from Embryo and Changing the Bones: Translating the Sonorous”

The second half of this book offers a variation on the dream of Yíngēlìshī 吟歌丽诗. What would it be like to translate sound itself? What if we could translate not only the meanings of poems, but their songs? The poems in this section arise from such an attempt by invoking Huang Tingjian’s (黃庭堅 1045-1105) notion of 夺胎 换骨or “evolving from embryo and changing the bones” which instructs poets to create their own poetry by either mimicking the content or the form of earlier poetry. An exquisite poet of the first order, Huang Tingjian, raised mimicry to the level of high art and philosophy by revealing that every act of mimicry results in an act of transformation. My translations follow both of Huang’s directives to mimic both the content (all translation does this) and the form by following all the basic aural constraints of Classical Chinese poetic forms (number of syllables, rhyme schemes, and tonal prosody).

Example:

客 舍 青 青 柳 色 新

kè shè qīng qīng lin sè xīn

guèst ìnn greēn greēn wil lòw sheēn

Yet these poems are also only figments of transpacific imagination: for even the same sounds (untranslated) are not the same sounds to those who hear them. There is no single, original song because everyone who hears it, feels it differently (especially those from different cultural and linguistic backgrounds). So why try… Ezra Pound would argue that one should “Fill [your] mind with the finest cadences [you] can discover, preferably in a foreign language.” But I am not sure we need to reduce these poems to such “usefulness”; instead in my earliest publication of Sinophonic English I wrote that “I write Chinese in English and English in Chinese, which, in its simultaneous success and failure, offers not a translation but a space for the translingual to be imagined.” (Chain, 2003, 109)

[Further examples & poems to follow.]

As sometimes happens in making electronic connections, I recently lost a year’s worth of email correspondence (from mid-2008 to the present), which I had been persistently storing in a constantly expanding inbox. My one apprehension is that this leaves me with a certain amount of interrupted communications & that a number of detailed & interesting attachments have also been lost in the process. I will try to catch up with this on my own, but if there are specific messages, requests, invitations, phone numbers, email addresses, or texts, manuscripts & attachments that any friends & readers want to get to me, you can reach me via email at jrothenberg@cox.net.

Otherwise Poems and Poetics will continue on schedule, as always.

J.R.

*

This stylized impersonating, non-producing figure begins to appear dramatically" in the works of Wilde and Jarry and in many ways in the "life and works" of a Félix Fénéon, who "creates at a distance" via anonymous newspaper faits divers (discovered to be his and republished posthumously as "Nouvelles en trois lignes" [News/Novellas in Three Lines]), pseudonymous articles in differing registers of language (working class argot, standardized French) in Anarchist and mainstream journals, unsigned translations, and the barely noted in their own pages of his editing of journals featuring the early efforts of rising stars of French literature. Quitting his camouflaged and concealed writing activities, Fénéon works the rest of his life as a seller in an art gallery.

The actual "works" of Fénéon, then, are not written objects per se, but anonymous actions, ephemeral pseudonymous "appearances in print," and the works of others which he affects a passage for in his editorship and translations, in his promoting and selling the art works of others. This "accumulation" which one finds "at a distance" in time as his "complete works," is often unobserved and unknown to his contemporaries, who know of him primarily via his "way of acting," his manner of dressing, his speech mannerisms, and as the public triptych of images of him existing as a painted portrait by Signac, a Dandy-pose photo and a mug shot taken when tried as part of an Anarchist "conspiracy." Fénéon's "identity as a writer" does not exist as "an author," but as a series of "performances," "appearances" and "influences," many of them "unrecognized" and "unattributed."

Ironically, it is his most "clandestine" activity—his Anarchist activities—which brings him the most in to the public and tabloid spotlight. As one of "The Thirty" accused and tried for "conspiracy" in a much publicized trial, it is Fénéon's severe mug shot that for a time presents his "public face."

The severe mug facing the viewer is actually producing a Conceptual Poetry "at a distance." By not penning a single line, by simply "facing the music" to which others pen the lyrics, Fénéon, in doing nothing more than facing the camera "capturing" his image, proceeds to enact a series of dramas "projected" on to him, a series of "identities," and "revelations" which use the documentary material to produce a series of mass-published fictions.

The possible prison term facing the "Félix Fénéon" in the inmate-numbered "anonymous" mug shot, "presents its face" to the viewer, a face "taken," "imprisoned" and "caught" by the image and its publicity. This publicized face facing camera and viewer and possible hard time, is "taken to be" the photo of the face of a being from whom the mask of the clandestine and conspiratorial have been torn off, revealing "the cold hard truth" of Félix Fénéon.

Facing trial, however, all that is learned of this imprisoned face is that it is "the wrong man, an innocent man." This fixed image, acquitted of its "sensational" charges, is revealed not as a truth, but instead as simply a mask, a mask operating like a screen or blank sheet of paper, onto which are projected the dramas, fictions and "think piece" writings of others. Nothing is revealed other than an "identity" which shifts, travels, changes from one set of captions to another. It is via these captions written by others under his image in the papers and placards, that Fénéon continues his "writing at a distance." Simply by facing the camera, facing charges, "facing the music," facing his accusers at trial and facing the verdict and judgment, Fénéon is "writing" a myriad captions, breaking news items, commentaries, editorials, all of which change with wild speeds as they race to be as "up-to-minute" as the events themselves are in "unfolding."

The professionals, these writers, these journalists and reporters of "reality," chase desperately, breathlessly, after the unfolding drama in which the mug shot is "framed," and in so doing produce texts of "speculative fiction," a serial Conceptual Poetry with as its "star player" a writer whose own texts are deliberately written to be unrecognized, hidden, camouflaged, unknown. And all the while, this writer writing nothing is producing vast heaps of writing via the work of others, as yet another form of camouflaged clandestine Conceptual Poetry, "hot off the press."

Rimbaud writes of a concept of the poetry of the future in which poetry would precede action—which in a sense he proceeds to "perform" himself. If one reads his letters written after he stopped writing poetry, one finds Rimbaud living out, or through, one after another of what now seem to be "the prophecies" of his own poetry. That is, the poetry is the "conceptual framework" for what becomes his "silence" as a poet, and is instead his "life of action."

In these examples, one finds forms of a "conceptual poetry" in which the poetry is in large part an abandonment of language, of words, of masses of "personally signed" "poetry objects," "poetry products." One finds instead a vanishing, a disappearance of both language and "poet" and the emergence of that "some one else" Rimbaud recognized prophetically, preceding the action--in writing—in the "Lettre du voyant," "the Seer's letter"—as "I is an other."

An interesting take on a conceptual poetry in writing is found in one of Pascal's Pensees, #542:

"Thoughts come at random, and go at random. No device for holding on to them or for having them.

A thought has escaped: I was trying to write it down: instead I write that it has escaped me."

The writing is a notation of the "escaped" concept's absence, its escape that is a line of flight that is a "flight out of time" as Hugo Ball entitles his Dada diaries. Writing not as a method of remembering, of "capturing thought," but as the notation of the flight of the concept at the approach of its notation.

Writing, then, as an absence— an absence of the concept. A Conceptual Poetry of writing as "absent-mindedness"!—A writing which does nothing more than elucidate that the escaping of thoughts "which come at random, and go at random" has occurred.

This flight of the concept faced with its notation—indicates a line of flight among the examples of Rimbaud—a "flight into the desert" as it were, of silence as a poet—and of Fénéon—the flight into anonymous writing of very small newspaper "faits divers" items punningly entitled "Nouvelles en trois lignes" (News/Novels in Three Lines), of pseudonymous writings in differing guises at the same time according to the journals in which they appear, and as translator and editor as well as "salesperson" in a gallery of "art objects," a conceptual masquerader among the art-objects embodying "concepts" and becoming no longer "concepts' but "consumer items." Fénéon's framed mug shot on to whose mug is projected a "serial crime novel," written by others and "starring" the mug in the mug shot, a writer of unknown and unrecognized texts who now vanishes into a feverish series of captions and headlines.

Anonymity, pseudonyms, impersonations, poets who write their own coming silence and "disappearance" as an "I is an other," the deliberately unrecognized and unrecognizable poet whose mug shot becomes the mass published and distributed "crime scene" for police blotters and headlines, speculative fictions and ideological diatribes, the writing which is a notation of the flight of the concept, the writing of non-writers who "never wrote a word," yet whose concepts may be found camouflaged, doubled, mirrored, shadowed, anonymously existing hidden in plain site/sight/cite—these nomadic elements which appear and disappear comprise a Conceptual Poetry in which the concepts and poets both impersonate Others and reappear as "Somebody Else," an Other unrecognized and unrecognizable found hidden in plain site/sight/cite.

[Excerpted from a longer essay/talk, “Conceptual Poetry and its Others,” written for a symposium at the Poetry Center of the University of Arizona, 29-31 May 2008. See also David Baptiste-Chirot's blog postings, both visual & verbal, at davidbaptistechirot.blogspot.com. More of his visual work has recently been posted on the new post-literate: a gallery of asemic writing.]

Outsider Poems, a Mini-Anthology in Progress (8): The Sermon As Poetry, from Reverend C. C. Lovelace & Zora Neale Hurston

INTRODUCTION (spoken)

“Our theme this morning is the wounds of Jesus. When the Father shall ast, ‘What are these wounds in thine hand?’ He shall answer, ‘Those are they with which I was wounded in the house of my friends.’ (Zach xiii. 6)

“We read in the 53rd chapter of Isaiah where He was wounded for our transgressions and bruised for our iniquities; and the apostle Peter affirms that His blood was spilt from before the foundation of the world.“

I have seen gamblers wounded. I have seen desperadoes wounded; thieves and robbers and every other kind of characters, law breakers, and each one had a reason for his wounds. Some of them were unthoughtful, and some for being overbearing, some by the doctor’s knife. But all wounds disfigures a person.“

Jesus was not unthoughtful. He was not overbearing. He was never a bully. He was never sick. He was never a criminal before the law and yet He was wounded. Now a man usually gets wounded in the midst of his enemies; but this man was wounded, says the text, in the house of His friends. It is not your enemies that harm you all the time. Watch that close friend. Every believer in Christ is considered His friend, and every sin we commit is a wound to Jesus. The blues we play in our homes is a club to beat up Jesus; and these social card parties….”

THE SERMON

Jesus have loved us from the foundation of the world.

When God

Stood out on the apex of His power

Before the hammers of creation

Fell upon the anvils of Time and hammered out the ribs of the earth

Before He made ropes

By the breath of fire

And set the boundaries of the ocean by gravity of His power

When God said, ha!

Let us make man

And the elders upon the altar cried, ha!

If you make man, ha!

He will sin.

God my master, ha!

Christ, yo’ friend said

Father! Ha-aa!

I am the teeth of Time

That comprehended de dust of de earth

And weighed de hills in scales

Painted de rainbow dat marks de end of de departing storm

Measured de seas in de holler of my hand

Held de elements in a unbroken chain of controllment,

Make man, ha!

If he sin, I will redeem him

I’ll break de chasm of hell

Where de fire’s never quenched

I’ll go into de grave

Where de worm never dies, Ah!

So God A’mighty, ha!

Got His stuff together

He dipped some water out of de mighty deep

He got Him a handful of dirt, ha!

From de foundation sills of the earth

He seized a thimble full of breath, ha!

From de drums of de wind, ha!

God my master!

Now I’m ready to make man

As-aah!

Who shall I make him after? Ha!

World within worlds begin to wheel and roll

De Sun, Ah!

Gethered up de fiery skirts of her garments

And wheeled around de throne, Ah!

Saying, Ah, make man after me, Ah!

God gazed upon the sun

And sent her back to her blood-red socket

And shook His head, ha!

De Moon, Ha!

Grabbed up de reins of de tides

And dragged a thousand seas behind her

As she walked around de throne—

Ah-h, please make man after me

But God said, No.

De stars bust out from their diamond sockets

And circled de glitterin throne cryin

A-aah! Make man after me

God said, No!

I’ll make man in my own image, ha!

I’ll put him in de garden

And Jesus said, ha!

And if he sin,

I’ll go his bond before you mighty throne

Ah, he was yo friend

He make us all, ha!

Delegates to de judgement convention

Ah!

Faith hasn’t got no eyes, but she’s long-legged

But take de spy-glass of Faith

And look into dat upper room

When you are alone to yourself

When yo’ heart is burnt with fire, ha!

When de blood is lopen thru yo veins

Like de iron monasters (monsters) on de rail

Look into dat upper chamber, ha!

We notice at de supper table

As He gazed upon His friends, ha!

His eyes flowing wid tears, ha!

“My soul is exceedingly sorrowful unto death, ha!

For this night, ha!

One of you shall betray me, ha!

It were not a Roman officer, ha!

It were not a centurion soldier

But one of you

Who I have choosen my bosom friend

That sops in the dish with me shall betray me.”

I want to draw a parable.

I see Jesus

Leaving heben with all of His grandeur

Disrobin Hisself of His matchless honor

Yieldin up de scepter of revolving worlds

Clothing Hisself in de garment of humanity

Coming into de world to rescue His friends.

Two thousand years have went by on their rusty ankles

But with the eye of faith I can see Him

Look down from His high towers of elevation

I can hear Him when He walks about the golden streets

I can hear ‘em ring under his footsteps

Sol me-e-e-e, Sol do

Sol me-e-e-e, Sol do

I can see Him step out up on the rim bones of nothing.

Crying I am de way

De truth and de light

Ah!

God A’mighty!

I see Him grab de throttle

Of de well ordered train of mercy

I see kingdoms crush and crumble

Whilst de arc angels held de winds in de corner chambers

I see Him arrive on dis earth

And walk de streets thirty and three years

Oh-h-hhh!

I see Him walking beside de sea of Galilee wid His disciples

This declaration gendered on His lips

“Let us go on the other side”

God A’mighty!

Dey entered de boat

Wid their oarus (oars) stuck in de back

Sails unfurled to de evening breeze

And de ship was now sailin

As she reached de center of de lake

Jesus was ‘sleep on a pillion in de rear of de boat

And de dynamic powers of nature become disturbed

And de mad winds broke de heads of de western drums

And fell down on de Lake of Galilee

And buried themselves behind de gallopin waves

And walked out like soldiers goin to battle

And de zig-zag lightning

Licked out her fiery tongue

And de flying clouds

Threw their wings in the channels of the deep

And bedded de waters like a road-plow

And faced de current of de charging billows

And de terrific bolts of thunder—they bust in de clouds

God A’mighty!

And one of de disciples called Jesus

“Master! Carest thou not that we perish?”

And He aroseAnd de storm was in its pitch

And de lightnin played on His raiments as He stood on the prow of the boat

And placed His foot upon the neck of the storm

And spoke to the howlin winds

And de sea fell at His feet like a marble floor

And de thunders went back in their vault

Then He set down on de rim of de ship

And took de hooks of his power

And lifted de billows in His lap

And rocked de winds to sleep in His arm

And said, “Peace be still.”

And de Bible says there was a calm.

I can see Him wid de eye of faith

When He went from Pilate’s house

Wid the crown of 72 wounds upon His head

I can see Him as He mounted Calvary and hung upon de cross for our sins.

I can see-eee-ee

De mountains fall to their rocky knees when He cried,

“My God, my God! Why hast thou forsaken me?”

The mountains fell to their rocky knees and trembled like a beast

From the stroke of the master’s axe

One angel took the flinches of God’s eternal power

And bled the veins of the earth

One angel that stood at the gate with a flaming sword

Was so well pleased with his power

Until he pierced the moon with his sword

And she ran down in blood

And de sun

Batted her fiery eyes and put on her judgement robe

And laid down in de cradle of eternity

And rocked herself into sleep and slumber

He died until the great belt in the wheel of time

And de geological strata fell aloose

And a thousand angels rushed to de canopy of heben

With flaming swords in their hands

And placed their feet upon blue ether’s bosom and looked back at de dazzling throne

And de arc angels had veiled their faces

And de throne was draped in mournin

And de orchestra had struck silent for the space of half an hour

Angels had lifted their harps to de weepin willows

And God had looked off to-wards immensity

And blazin worlds fell off His teeth

And about that time Jesus groaned on de cross and said, “It is finished”

And then de chambers of hell explode

And de damnable spirits

Come up from de Sodomistic world and rushed into de smoky camps of eternal night

And cried “Woe! Woe! Woe!”

And then de Centurion cried out

“Surely this is the Son of God.”

And about dat time

De angel of Justice unsheathed his flaming sword and ripped de veil of de temple

And de High Priest vacated his office

And then de sacrificial energy penetrated de mighty strata

And quickened de bones of de prophets

And they arose from their graves and walked about in de streets of Jersualem

I heard de whistle of de damnation train

Dat pulled out from Garden of Eden loaded wid cargo goin to hell

Ran at break-neck speed all de way thru de law

All de way thru de prophetic age

All de way thru de reign of kinds and judges—

Plowed her way thru de Jordan

And on her way to Calvary when she blew for de switch

Jesus stood out on her track like a rough-backed mountain

And she threw her cow-catcher in His side and His blood ditched de train,

He died for our sins.

Wounds in the house of His friends.

That’s where I got off this damnation train

And dats where you must get off, ha!

For in dat mor-ornin’, ha!

When we shall all be delegates, ha!

To dat judgement convention, ha!

When de two trains of Time shall meet on de trestle

And wreck de burning axles of de unformed ether

And de mountains shall skip like lambs

When Jesus shall place one foot on de neck of de sea, ha!

One foot on dry land

When his chariot wheels shall be running hub-deep in fire

He shall take his friends thru the open bosom of a unclouded sky

And place in their hands de hosanna fan

And they shall stand round and round His beatific throne

And praise His name forever.

Amen.

COMMENTARY

after J. Rothenberg & G. Quasha, America a Prophecy: A New Reading of American Poetry from Pre-Columbian Times to the Present, 1974

A vast area of American poetry is to be found in the Black oral tradition. The sermons of Black preacher-poets, for example (commonly set up in verse lines in the printed versions) are instances both of speech in complex motion and of a process of ongoing mythos, i.e. of ancient story made or remade in the telling. The contemporary African-American poet Tom Weatherly wrote: “Our tradition is composed of those work songs, field hollers, gospels, and blues. … That’s our poetry, our tradition, my main main, and if you put it down, you put down most of what is good in American song lyric and poetry, and you put down most of the base I build on.” The sermon-poem above follows Zora Neale Hurston’s transcription and reconstruction after an oral performance by Reverend C. C. Lovelace on May 3, 1929, in Eau Gallie, Florida. Her notes to the work read further: “The colored preacher, in his cooler passages, strives for grammatical correctness, but goes natural when he warms up. The ‘ha’ is a breathing device, done rhythmically to punctuate the lines. The congregation wants to hear the preacher breathing or ‘straining.’”

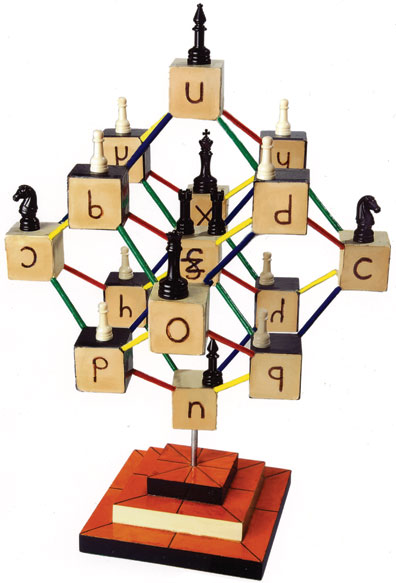

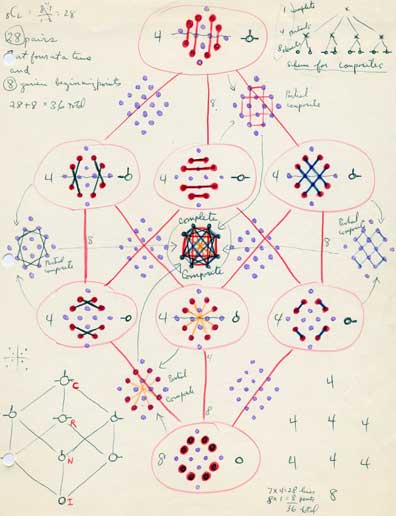

In 1953, while working a hotel switchboard, a college graduate named Shea Zellweger began a journey of wonder and obsession that would eventually lead to the invention of a radically new notation for logic. From a basement in Ohio, guided literally by his dreams and his innate love of pattern, Zellweger developed an extraordinary visual system called the “Logic Alphabet” in which a group of specially designed letter-shapes can be manipulated like puzzles to reveal the geometrical patterns underpinning logic. Indeed, Zellweger has built a series of physical models of his alphabet that recall the educational teaching toys, or “gifts,” of Friedrich Froebel, the great nineteenth century founder of the Kindergarten movement. Just as Froebel was deeply influenced by the study of crystal structures, which he believed could serve as the foundation for an entire educational framework, so Zellweger’s Logic Alphabet is based on a crystal-like arrangement of its elements. Thus where the traditional approach to logic is purely abstract, Zellweger’s is geometric, making it amenable to visual play.

SUMMARY

The narrator, living in a duplex, believes that her next door neighbor has committed a crime (perhaps a murder or the sexual torture of women). One day, walking out of her back door, she enters a red barn that she has noticed but never entered. Once in the barn, she discovers a small hole through which she can spy on her neighbor. She is joined by her friend, Jim, who helps her to build optical devices to improve her surveillance activities. Meanwhile, another friend, Marilyn, who has suffered a concussion that has made her psychic, begins to travel towards the barn, hoping to arrive in time to warn Jim and the narrator of danger. The identity of the narrator is not simple; all of the characters seem sometimes to be part of a fractured self. Even Gary and the mysterious women he might or might not have imprisoned in his house are part of the self of the watchers.

In Part II, the narrator finds herself naked and a prisoner in a completely empty room without windows or doors. Then the rooms progressively change: objects appear, a door, a window. She is bothered by the voices of three characters: Anise, Mercury, and the Technician. Unsure whether these voices come from outside or inside her head, she tries to communicate with them, hoping that they are her rescuers and not her captors. In Part III, the narrator finds herself back at the barn. Everything that she thought had happened before her imprisonment is proved false or in doubt and the circle of confusion and ambiguity begins again.

METHOD

“Surveillance” was written using a systematic process. Both Robinson and Zweig, reading whatever books they found interesting (fiction, non-fiction), collected phrases, 19 at a time, sending them to each other. Each set of 38 phrases became a chapter. Using a variety of rules to control the creation of the text, Robinson and Zweig had to use all 38 phrases. Thus, in any given chapter, repetitions in language are hidden in the text as a structural skeleton. One of the strengths of this process is how the plot, characters, descriptions (which have often been planned in advance) are subverted by the necessities of the found phrases. Pushing against the will of the writer, the language forces digressions; or the writer pushes back insisting on characters, plot, descriptions.

EXCERPT ONE (from Chapter 1)

Because I lived in a highly contaminated inner world, I hadn’t noticed the barn for the first few months of my stay in upstate New York. The red barn was merely a backdrop for crows and an occasional rabbit; that is, before the incident that foreshadows my obsession with a certain kind of alterity that can only be caused by the play of light and shadow in just such a red barn.

I had every intention of leaving, and with my finger on the map of the city, I was idly inventing neighborhoods in which to live. I had no idea what orgy of treason festered on the other side of my bedroom wall. My neighbor, a large red-faced man named Gary, was known for his complicity with the police in a scandalous gambling den on the south side of town.

When I finally entered the barn, for no other reason than that it was there, I noticed for the first time the invisible nervous presence of the accomplice. Although I had never seen anyone enter the barn, the indentation left by his weight at the end of the sofa haunted me as though someone was almost always looking over my shoulder.

I crouched in the neighborhood of the beckoning cat and stroked him down his silky spine. I remembered my friend Marilyn saying that vision was central to three of her explanations. Marilyn was known for her desire to control everything by rational means, but had suffered from a severe concussion (I found this out afterward); she had intense and unpredictable bouts of dizziness accompanied by blurred vision and irrational insights.

She had told me about a week before I entered the barn that something would happen to me, something very important and startling, at about twenty to six or ten past four. I did not know that she had already decided to leave Paris that evening.

Every time, every day, when I think back to that uncanny concatention of events, I think of her left eye twitching like it did in the grey light of November when she was about to speak.

I looked at my watch and suddenly remembered that it was in a restaurant that he said it: “The flesh is weak, but can be made to obey.” I’m speaking of his voice, so familiar, like an old 78rpm phonograph record.

It was still dark when I reached my rocks, the ones I had placed carefully on the side of the barn where I had seen the small hole. I knew that I was going to spend a long time in a present fixed with the help of a past.I desperately hoped that Marilyn could hear my thoughts as though they were her own. I thought I heard a sigh, a moan, perhaps a scream, but wasn’t able to interpret it.

EXCERPT TWO (from Chapter 1)

…Imagine it …: a room with no windows or doors. Smooth white walls, floor, ceiling. A woman, naked, lying on the floor; then, sitting huddled in a corner; then, pacing, feeling the walls, knocking for hollow places, anything that might provide the zone between life and death. One flourescent light bulb behind a piece of translucent plastic in the ceiling, no switch in the room, nothing to stand on to see if the plastic can be removed. A kidnapping: those who have mapped its path no where in view.

If I had been taken under protest, I would have been imagining my escape. But then, in this room, I felt nothing but a kind of deep apathy (probably the result of the drugs they had given me) and it wasn’t until later that I began to question the puzzle of this room…. There was no way in or out. Now, I think that the only way they could have gotten me into that room was if it was a room whose walls separate absolutely from each other, like the flat modules of a toy house….

I’m certain it was in the quiet room that I heard the sound of wings, of a great bird hitting itself against a window or a wall. Or perhaps a moth as big as the palm of my hand.

I attribute my dream not to death but to sadness. Jim was alive, come back from the dead. I ran over and hugged him, then couldn’t get enough of touching him. I stroked his head and shoulders and arms. No one had told him about the events that had taken place after his death, the memorials, the conversations between friends. I said: “Did you know that when we did the memorial for you in San Francisco, on the leaflet, we used that photograph you had taken of yourself sitting up in a coffin?” “Really,” he said, “no one told me. How wonderful.” Then, I suddenly realized that he must have been buried and I asked him how he got out of the grave. At that moment he turned into Avital Ronell. She was standing, leaning against a pillar. “Bodies are buried in layers in the ground,” she explained, “and they put in these long metal breathing tubes so that the earth can breathe.” She paused, “And something I read recently ruined me for life. Do you know that we fugue into consciousness over and over again after we’re dead?” This dream draped itself over me. I felt clothed.

[PUBLICATION HISTORY. Excerpts from “Surveillance” were performed by Ellen Zweig as part of the performance piece, “Absent Bodies Writing Rooms”, which premiered at the Center for Music Experiment, University of California, San Diego (April, 1995) and toured Australia in July and August of 1995. Excerpts were also published in 13th Moon, Vol.13, Nos.1&2, 1995; Black Ice, No. 10. 1993; and Trivia, No.19,1992. Along with other writings and performance scenarios, excerpts from “Surveillance” can also be found on Ellen Zweig’s web site: http://ezweig.com/]

The following account of Economou’s masterwork was originally published in The Times Literary Supplement, July 24, 2009, and is available in its original format at http://entertainment.timesonline.co.uk/tol/arts_and_entertainment/the_tls/article6723015.ece

A Nabokov of the ancient world: what a millennium of repressed, cock-happy scholars can do to an obscure Arcadian poet

Ancient literary texts have a habit of turning up at historical junctures. When Alexander the Great captured the Lebanese city of Tyre in 332 BC, one of his soldiers found a tomb outside the city. Alongside the coffins was a cypress chest, which turned out to contain a marvellous novelistic account of adventure, magic and love, much of it set beyond the mysterious north-Atlantic island of Thule (Iceland?). In AD 67 a mighty earthquake shook the island of Crete, exposing an underground cavern near Knossos; in that cavern was a precious text, written in “Phoenician letters”. The manuscript eventually ended up in the hands of the emperor Nero, who summoned his experts to decode it. Amazingly, it turned out to be the journal of one Dictys, a participant in the Trojan War. What are the odds on that?

In fact, the chances are pretty high, at least in a certain tradition of fictional writing. The first example comes courtesy of Antonius Diogenes, author of the extravagant fantasy The Wonders Beyond Thule, the second from an equally fictitious text of the Roman imperial era, the anonymous Journal of Dictys of Crete. Classicists, particularly after Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose, are practised readers of such “pseudo-documentarism”. So when a book of poems by a previously unknown writer turns up on your desk, the antennae immediately begin to twitch – especially when the story of their rediscovery is as thrilling and captivating as any fiction.

According to this ingenious pastiche of a scholarly edition, Ananios was born in 399 BC (the year of Socrates’ execution), in the obscure Arcadian town of Kleitor. He composed his vibrant, life-loving poems of sex, drink, local topography and cabbage in an era of huge social upheaval, not to mention literary sophistication (he turns out to be our earliest witness to the impact of Thucydides). Of the poems themselves, we have forty papyrus fragments: apart from poems 15 and 17, most of them are mere scraps. Poem 41, for example, reads simply:

]awe[ ]none[ ]oh yes[

What lends this book its power and panache, however, is not so much the morsels it claims to preserve from antiquity’s table, but the extraordinary story of Ananios’ razor’s edge “survival” and “rediscovery”. The important question is not what you and I make of these meagre fragments, but what – according to George Economou – more than a millennium of inventive, zealous, insane, repressed, evangelical, cock-happy, racist, murderous scholars can do to them, given an inch or more. The narrative that he weaves in Ananios of Kleitor is dominated by alpha males exalted and humbled (and worse) by the effects wrought by their egos and intellects. This is the story of how words lose their meanings and gain new ones through the ages.

Read and savour this book from beginning to end. Certainly, it mimics the rebarbative conventions of scholarship: “Introduction”, “Note on Spelling”, “Notes on the Introduction”, translations of the fragments, “Reception”, “Endnotes”, “Index nominum”. Economou maintains, poker-faced, the fiction that we will “consult” the notes to support our readings in the text, or even “honor the well-worn practice of skipping them altogether”. But the real pleasure emerges from a page-by-page reading, which gradually discloses the identity of the ancient, medieval and twentieth-century actors who have engaged with this text, the web of imagery that binds them together and the interconnectedness of their stories.

From the ancient world, the cast list includes Ananios himself (barely visible through the veils of time); the “anonymous Alexandrian”, a Hellenistic commentator who survives on papyrus only; and Theonaeus, the third-century ad polymathic author of the Deipnopaideiai, or Games for Dinnertime (a slight mistranslation). All of these are figures who might conceivably exist, in a classical parallel universe (Theonaeus, for example, is a near-anagram of Athenaeus, the real author of the Deipnosophists). Next, chronologically speaking, comes my own favourite character in the book, the sixth-century Christian cook and rhetorician Kosmas Logothetes, whose grapplings with Ananios’ eroticism convey brilliantly, and hilariously, early Christians’ schizophrenic battle between morality and logoerotic pleasure:

If you seek an example of homoiosis, you may find it, at peril of your immortal soul, in the first of two lines, which Ananios meant to insert into the middle of a poem, worse even than his, by Rufinos, famous for his supposed judging in beauty contests over the private parts of loose women:

Melite’s can be played like Hermes’ lyre

What Ananios says may be done with what lies between Melite’s thighs in the next verse, it is my sacred obligation to keep to myself.

Theophanes, the eleventh-century “mad monk of the Morea”, is also hilarious, inveighing against the Byzantine dynasty of his day, using Ananios as a cipher for sexual and culinary immorality (he is particularly upset by the misuse of fish).

A grimmer story, however, clusters around Ananios’ twentieth-century rediscoverers: Anastas Krebs, a crazed but insightful German historian of ancient warfare, whose Romantic Hellenism inspires his quest for Ananios; Sir Michael Sewtor-Lowden, a friend and sometime fellow traveller of Krebs in Greece, who holds a distinguished chair in Cambridge; Jonathan Barker, a graduate student of Sewtor-Lowden, who visited Krebs in 1951 and was entrusted with the latter’s studies on Ananios; and Hugh Sydle, another of Sewtor-Lowden’s graduate students.

The plot unfurls amid hints and misdirection, most of all in the twentieth-century correspondence, which is lovingly “reproduced” here. The arrangement of these letters is riotously non-linear. They start as they were acquired (he claims) from Barker’s widow in reverse chronological order; but even the reversed order is after a while discombobulated and reverts without warning to forward chronology. This plays to the book’s central theme, the interconnectedness of fragments of existence, particularly across time. Jumbled letters, papyrus fragments, excerpts from larger books, the academic edition designed for “consultation” – these should in principle butcher the narrative, but Ananios’ text turns out to be possessed of a strange ability to transcend time. History repeats itself, comically, tragically, unpredictably. At the end of one inconspicuously dull biographical endnote, the narrator spasmodically switches into philosophical mode and comes up with what looks like a vade mecum for the whole book:

We have been spilled into an enormous chamber wherein life continuously echoes art and art life, resounding through volumes of ironies bound in a plenitude of tongues. Some hear nothing. Others strive to link their strains to fulfilling termini in the cosmic din, transforming and modulating them into a manner of music, or the illusion thereof.

Is this the key to reading Ananios of Kleitor? Yet it looks so much like another brilliant parody of academic pretension.

The setting for Ananios’ rediscovery is not the siege of a Lebanese city or a Cretan earthquake, but the occupation of Greece during the Second World War. The narrative centres on Krebs’s complicity in Nazi war crimes in Greece, on Sewtor-Lowden’s appropriation of Krebs’s work from Barker, and on Barker’s gradual sidelining. Economou’s narrator, playing the unworldly, rationalist classicist to perfection, sides with Krebs against the shameless plagiarist Sewtor-Lowden. But Sewtor-Lowden’s last letter to Krebs reveals a different figure, denouncing his friend for his “powerful desire to rewrite history”, which encompasses both his account of Nazi executions in Greece and his famous work on a battle outside Corinth in 393 BC. This final letter also contains a shocking and unforeseeable plot twist which, like Kosmas Logothetes, I shall treat it as my sacred duty to conceal.

Sewtor-Lowden and Krebs are divided by history and ethics, but they share more than they initially knew. As young men, both travelled to Greece in search of the world of lyric poetry, a land of beauty, exquisite poetry and sex without consequence. Both in due course betray themselves in the most loathsome ways, and find themselves enmeshed in a “tragic chain of events”. Sewtor-Lowden’s last sentence is “Through all of this, have we not . . . been terribly Greek?”. The adverb “terribly” is, of course, vigorously ironic.

The fragmentary Ananios of Kleitor is an almost blank screen on to which others project their own fantasies, with the same rapacity that their compatriot soldiers and tourists approach the people of modern Greece. Krebs (as plagiarized by Sewtor-Lowden) reconstructs the fragmentary poems, so that they become more his poems than Ananios’, and reflect particularly his own repressed sexual urges for “a pro from Corinth”. Ananios of Kleitor thus practically is Anastas Krebs. This kind of play with names and naming is a running theme throughout. First, there is the constantly invoked risk of confusion with the other Ananios, one who actually exists (four of his fragments are preserved by Athenaeus). It gets worse. The mad monk Theophanes is so excitedly shocked by Ananios that he insists on distinguishing him from the pious, biblical Ananias, and proposes instead to transform “alpha into omicron”. There is nothing to help the reader here, but we have to conclude that this makes him “Onanias” – or “wanker”. “Ananios” of course also suggests “anon” (as in the “Anonymous Alexandrian”, his earliest extant commentator). Both his name and his toponym also invite all sorts of obscene cerebrations (never Google “Clitor”, the Latinized form of the town’s name).

So, Ananios turns out to be an imaginary object of desire, endlessly recreated by his later readers. But Ananios of Kleitor is not just a spoof. The scholarly ventriloquism and the command of details are impressive, certainly, but the fictitiousness (for example “Kythe College, Cambridge”) is too visible for any reader to be fooled into mistaking this world for ours. What it actually is, however, is harder to define: perhaps equal parts academic parody, postmodern romance and prose poem, a kind of ancient-world equivalent of Nabokov’s Pale Fire. Some sequences are uproariously funny, but others are provocative, moving or horrifying. It draws to the surface the absurdity, myopia and arrogance of academic prose and the awful conjunctures of history and scholarship; but it is also an affectionate and humane tribute to the power of poetry to lend new meanings to new readers’ lives across the ages. A wonderful book.

George Economou

ANANIOS

Ananios of Kleitor

144pp.

Shearsman Books.

Paperback, £9.95 (US $17).

978 1 84861 033 5

Tim Whitmarsh is E. P. Warren praelector in Classics at Corpus Christi College, Oxford. His books include Greek Literature and the Roman Empire, 2001, and Ancient Greek Literature, 2004.

Outsider Poems, a Mini-Anthology in Progress (7): David-Baptiste Chirot, a Range of Responses/Questions

Arthur Rimbaud, “Alchemy of the Word”

It might be very interesting to also have some --perhaps--who knows----at any rate some examinations investigations questionings of "outsider poems"—“outsider poetry" in an anthology of this kind----

Such as when does one begin to find the lists of “outsider Poetry” such as Rimbaud’s beginning to first appear—in Rabelais or Villon, or among the romans or Greeks--??—

Among the “idées reçues” of Flaubert’s dictionary of them compiled by Bouvard and Pecuchet—among the anonymous Faits divers of Félix Fénéon in 1906—all the disappeared and forgotten works which begin to beckon to one from out of the shadowy little known or visited areas where Outsiders are said to dwell—hidden inside fictions as among camouflaging and codes, so as to remain hidden until the “right person comes along and finds them . . .” a soon to arrive or quite distant M Champollion to translate them from Outsider languages—” ( these works while considered "classics" within themselves ask questions which may be of use in thinking on "outsider poetry--")

The usual journalistic questions come swarming to mind----what is Outsider Poetry--when did it first appear--by whom--anonymous or known--where--and then why--why this anthology, why now, and what for--and why or when or how is the editor interested in this--new territories to conquer?--to open up things not already opened or come to mind--and for whom one may ask other than as a corollary of textbooks already taught and used by poets also--as yet another tome creating a whole new field of teaching jobs and essay production and commentaries and so on--which accompanies the outsider's procession into the insiders' worlds-- . . .

Perhaps the simple asking of basic journalistic questions is a good way to start some thinking about the "outsiders" and who and why they are and where and when and which to put inside an insider collection of outsiders . . . / to generate some ideas and evermore questions--else one is just going along with a kind of blurry image in the mind of something called willy nilly an outsider by all manner of qualifications without asking oneself what the heck am i actually thinking about--in considering this or that poet

so there is a lot of work and fun and creation to be done with all these questions and their swarming descendants and proliferating extended families for sure--

Yes--as very many of these questions, investigations, perhapses and wonderings can and do swarm into the light like moths disturbed from their somnolence in the quiet darkness of libraries where the book worms create a new form of writing which is the literal consumption of the texts—creating strange labyrinthine passages which re-write whole sections of poetry and devastate fields of prose—and mimic in their way certain acts of reading which eat their way through texts leaving behind them an erased zone someday to be part of palimpsests of dust, grime, or jottings when the blank pages are reused by the recycling minded as the “blank spaces” to fill with a diary, or an outline of an essay on the manner in which locusts resemble readers devouring texts, and in a much more systematic and ruthless manner than mere book worms or moths resembling worn out scraps of old carpeting imbued with the dust of many fortunately departed days--

Yes, regarding an anthology of Outsider Poetry one might well ask--How much does this idea borrow from or diverge from the original conceptions of Outsider work that began early in the late 19th-early 20th century with artists trying to get "outside" their own culture via arts from other cultures (Gauguin, Van Gogh, Picasso etc) or via the discovery of a "Sunday Painter, a naif" like Rousseau who could also be included in "art,", or art from children (Kandinsky, abt 1905) and then art from the mentally ill (Prinzhorn, 1922) . . . or the Surrealist uses of the dream and exquisite corpses and automatic writings (precursors perhaps of the machine programmed writings of today used to “get outside of the lyric I”--) or the uses of drugs and alcohol to create “out of the same old same old mind experiences” so to speak—and then Dubuffet’s concepts and collection of Art Brut first announced in 1947—

There are a huge number of ways to examine what is "outsider poetry" depending on the cultural construction, as well as the academic, poetic, social constructions that one brings to the concept, the idea, the image of what "outsider poetry" is or is not, or could be etc—

There’s also an immense worldwide phenomenon across many media and arts of "the outsider artist and his/her works" in art magazines, lit mags, among musicians and record collectors, buyers of "primitive" or "self taught" artists' creations--all of these have contributed to the vast explosion of a now very widespread popular appreciation of and deliberate creation of "outsider works" as an "underground, legendary source" of some of the works considered to be "extraordinary, different, outside the usual run of things, brut"--from the past, the present--and maybe even in a sort of Futurism based on the sense that what exists in the Present is a "ruins in reverse" of the future--when the present is taken to be a "construction site" from which buildings emerge—

Yes, out of art brut and outsider works for a long time have the professional or amateur “artists” of the non-brut variety found inspiration, solace, the recognition of a “fellow spirit,” Just as they do with non-Outsiders except the Outsider comes with far less cultural baggage—at least for a while--

What then would make "outsider poetry" different from the other "outsider works and artists?" What then might be the meta literature of outsider works like that of Roberto Bolaño's book Nazi Literature of the Americas, whose last section led to the novella Distant Star in which exist such "outsiders" as the Barbaric Writers, fan zines offootball teams that aspire to a kind of super aggressive poetry, bizarre motorcycle white power club mags on badly printed low quality papers----and so on-or those produced as de luxe “vanity editions” to the select few--

Then there are the various approaches to what a French writer has called "The Literature of the No," which I have worked in for a while now and been ecstatic to begin finding it in the work of other writers such as Enrique Vila-Matas and M. Bérubé--as well as a long tradition going back especially to some examples in the travel Literature of the 17th century---this is the "Bartleby and Company" branch of the unwritten and--all the same perhaps readable texts--the areas of the unreadable which will someday emerge as readable or the unwritten which is ultimately written by a completely different person as though "taking dictation" from an unknown source--a voice, a trace among spider webs "blowing in the wind"--

Then there could be the question of the history of the recognitions of an outsider poetry at different epochs--say beginning at one period and ever since the uses and interests of such an Outsider text as the confessional writings of the condemned serial killer Gillesde Rais, or that of "peasant writers" in several European countries "coming to light" during the Age of Enlightenment--

Speaking in tongues--might have found through its immensely long history various ways other than Zaum which attempted to create/included in itself something akin to this in writing?--

Then there is the language and writings of it given to puppets, Guignol, the works written with much use of slang like Celine and Genet--and ones who are more extreme by far--so many many others now in the usa alone--in which there’s the return to the kind of jargon used by Villon which not long after begins to decay in its being able to beunderstood and turns then into a form of writing "outside" the very words around it—

one could include as Outsider Poetry could one not the immense amount of writing which is right on the paintings and objects of art brut—which is quite like the book of Kells as redone say by the pre-perspective “primitive” painters of Italy, whose works are like forerunners to comic strips—with the writing of what the personages are saying underneath the image, esp of Holy persons, the Holy Family and Saints and so forth—

(I am for the most part limiting this to Western examples—as that is what i am more familiar with--)

Outsider writing/poetry could be that done in Mail Art by the writings and stampings collaged images and quotations from magazinzes and newspapers –

The question of what is Outsider Poetry—and according to whom, and why—and at what time in art historical and in literary historical and in historical time—all of these play a part do they not in considering what may or may not be “Outsider poetry—”

In Visual Poetry, my works are accepted as “visual poetry” though at a kind of extreme (“the dirtiest of the dirty” according to Geof Huth and, with Bob Cobbing, part of the “extreme school of Quick’nDirty” by jw curry)—

But when one asks about where one might display them, as soon as they are moved from one realm (poetry, visual poetry) to another—the visual strictly, they become immediately called “art brut” or “punk art brut’ etc

In writing how then does one qualify an outsider poet—by many criteria of a person’s life and influences and the effects methods and interests and style of the writing, a person like Bill Burroughs and myself are lumped as a form of “outsider” writer off in the darker areas close to the “Poètes Maudits”—

Yet one might also say—yes but –despite the other qualifications these birds pass without question, what about other factors involved--??—the same with jean genet or a writer like Mohamed Choukri who was illiterate until age twenty and went straight from illiteracy to writing in classical Arabic, as genet wrote in Classical Racinien French—

Yet they are considered also Outsiders due to the backgrounds, life story—

So it is all a much more complex and swarming area—to really extend the questions of I wd think—or hope—because otherwise why do an anthology of outsider poetry now, at this moment other than perhaps, since writing is always fifty or more years behind painting—

To only now “catch the wave” of a guaranteed mass appeal--and throw together an anthology of something vaguely called an “Outsider poetry” –

Isn’t it important to present some ideas of what Outsider is in poetry, what might be different from it than in other arts—or—to make use of these for forms of thinking on works that aren’t outsider ones—either what I call “Fauxk Art” type writing or the neo-Brute , or the Nostalgic poetics of the neo-Naugahyde poetry of the ranch houses of yesterday and their contribution to a “fauxk rusticity” or a “kind of ruin of the images of the old west” down to the fake Fauxk --yes, one can indeed fake the fauxk!!!--wagon wheel in the corner to be immortalized in a harsh yet ‘swinging’ meter based indeed on Western Swing music—

That is, one can INVENT all manner of outsider Writers just as Borges did to a good and powerful extent and Bolaño, Bérubé, Vila-Matas and myself invent them whole sale—out of whole cloth—because even the fictional or perhaps even more so the fictional becomes a kind of “avant-garde” leading the way into these “unknown realms existing all around one and hitherto unnoticed”—

Because the elasticity of the fictional as it operates among the actual—opens gates there one had never noticed at all—like the place in a wall in a H G Wells story which suddenly for passersby produces a door opening to a completely Other World--

Or has perhaps gleaned from the art music and various other outsider lit examples of the past—

That is part of the challenge of this kind of project—for sure—

[David-Baptiste Chirot's own blog can be found at http://www.davidbaptistechirot.blogspot.com/, & more of his work is scheduled for future postings on Poems & Poetics.]

There was a time in the increasingly distant past when I found it necessary to place great stress on & to investigate the possibilities of a poetry without [outside of] writing. At a time when Dennis Tedlock & I & others were launching a specific ethnopoetics, we saw our work involved, before all else, with bringing to light & defending those deeply imbedded oral traditions that accounted for the greater part of people’s attempts to shape language as a vehicle for gnosis & transformation. And right from the start – how could it be otherwise? – I found myself caught in an assumed dichotomy between speaking & writing.

There is no doubt that we had presented a critique of writing as such – at least of what we saw as a kind of authoritarian literalism for which writing was the necessary instrument. The easy assumption by those who didn’t want to hear from us (and by many of those who did) was that we were divorcing ourselves from writing or from literacy, the victims, so to speak, of our own either/or mentalities. In the face of this, as I pointed out to William Spanos in an interview (circa 1975), I recognized myself even then as a writer & as a maker & creator of books – saw writing & books as the principal vehicles in my life as a poet.

[Quote] I don’t think that writing is the ultimate cause of our troubles, but that writing itself comes about [initially] in response to a more fundamental change in human organization: a need to institutionalize laws, to control change & the uncertain acts of the individual, in the name of a tribe, of a class, of a nation, of a god, whatever. ... I have never thought of “oral” ... as my personal shibboleth, & I probably use it much less than you suppose. Because I happen to write – as do the other “oral poets” you mention elsewhere -- & I’m not going to undo that [now].

That, however, was not the point that needed to be made at the time, and I dedicated myself for a number of years to the restoration of voice and presence as matters of comparable value to our practice.

I have gone over this a number of times in the past and I’ll return to it later when I read from the pre-face to A Book of the Book. But to move it forward now, let me point out that the title of this talk – the subtitle at least – is meant as a gesture toward Edmond Jabès, another of the poets (and a very great one) who was willing to enter with us into the ethnopoetic discourse. In 1975 I had managed, with the crucial involvement of Michel Benamou, to organize an international symposium on ethnopoetics at The Center for 20th-Century Studies in Milwaukee. The first of two such symposia, it focused on a number of contemporary concerns, but with the greatest intensity perhaps on the possibilities of oral poetry and (as a counter to that) on the problematics of writing. (“Otherness” and “identity” were likely the other two major questions.) By the time of the second symposium – 1983 at the University of Southern California’s Center for the Humanities – it was my desire & decision to open the range of the discourse to consider an ethnopoetics of writing. Put in terms of the larger project, “the intention of the conference,” I wrote, “was to take the discussion of ethnopoetics beyond its earlier, restricted definitions.” And later, in my introduction to the conference: “An expanded ethnopoetics would include an ethnopoetics of writing / of the book.”

With this in mind I turned to Jabès as one of the anchors of the conference. For it was in Jabès, as in no other poet since Mallarmé, that the Book, the repository of the written text, became the key term [along with the word “jew” he tells us], the unifying metaphor of both his poetry and his poetics, referred to often, binding all. Yet Jabès was also a poet of the voice – in the tradition from which he and I both sprang, however separated from it we thought ourselves to be. This was the concept of both a written and an oral torah [a written and an oral way] that led back to a common source in mind or spirit – to that which makes us “human,” and in the view of some, “divine.”

In turning to Jabès, who had been a friend since the late 1960s [early 1970s?], I had in mind – in a very personal way – the title of one section of his Book of Questions – “Le retour au livre” [The Return to the Book]. For the 1983 symposium, he gave his talk the title: “From the Book of Books to the Books of the Book.” What he spoke of there rhymed perfectly with the major thrusts of the gathering – a question of the relation between the spoken word & writing; of memory tied to language, music, sound, noise, silence; of whether we are the product of one culture or of several; of the way in which a written text is a victory of the anonymous [or not] – all pertinent to the poetics we were then constructing [the questions we were then discussing].

The book – for Edmond as for Mallarmé before him – is the book writ large, for which the book-in-hand is a valid but fleeting instance. (A kind of platonic Book [capital B] and book [lower case].) It is also something else that he spoke of – the “mythical book, the Book of books ... inside every writer ... [and] which he vainly tries to approach in each of his works.” This Book of the Mind, which is also “the book of the universe ... which we try to copy ... [and which] cannot be a ‘closed’ book,” brought me back to the image of the “great book,” “the Book of Language” envisioned by the Mazatec shamaness María Sabina. In a well-known account of her initatory experience, she describes her encounter with the Principal Ones, the tutelary beings of traditional Mazatec culture:

On the Principal Ones’ table a book appeared, an open book that went on growing until it was the size of a person. In its pages there were letters. It was a white book, so white it was resplendent.

One of the Principal Ones spoke to me and said: “María Sabina, this is the Book of Wisdom. It is the Book of Language. Everything that is written in it is for you. The Book is yours, take it so that you can work.” I exclaimed with emotion: “That is for me. I receive it.”

In 1982, the year before the second Ethnopoetics symposium, I assembled (in collaboration with the poet and folklorist David Guss) a first collection of works about the book & writing. Presenting it initially as an issue of my magazine, New Wilderness Letter, and later in a reprint by Steven Clay and Granary Books, I took the cover-all title from Mallarmé’s essay, The Book, Spiritual Instrument. As Mallarmé – in my mind at least – was one pivot for the work, María Sabina, though not included, was the other. In other words, what I was aiming for was a reconciliation of a modernist (experimental) poetics with my sense of a necessary ethnopoetics to which it related. As stated in my Editor’s Note:

In an age of cybernetic breakthroughs, the experimental tradition of twentieth-century poetry & art has expanded our sense of language in all its forms, including the written. While doing this, it should also have sensitized us to the existence of a range of written traditions in those cultures we have named “non”- or “pre”-literate – extending the meaning of literacy beyond a system of (phonetic) letters to the practice of writing itself. But to grasp the actual possibilities of writing (as with any other form of language or of culture), it is necessary to know it in all its manifestations – new & old. It is our growing belief (more apparent now than at the start of the ethnopoetics project) that the cultural dichotomies between writing & speech – the “written” & the “oral” – disappear the closer we get to the source. To say again what seems so hard to get across: there is a primal book as there is a primal voice, & it is the task of our poetry & art to recover it – in our minds as in the world at large.

Writing and the Book, then, from a perspective that hopes to bring together the experimental and the ethnopoetic – and with much left out in between. All of this was something on which I continued to ruminate, until (it now seems to me) the idea of writing and the book had struck a balance in my mind with voice and presence. And beyond The Book [as] Spiritual Instrument, there was an ongoing regard for the book as a material object and – as Steve McCaffery and bp Nichol have it in a well-known essay – the book as a machine, whose fine technology has still not been truly superceded by its vaunted virtual replacements.

With A Book of the Book, Steven Clay gave me the opportunity to go over those concerns and to extend the work of the earlier collections to a wider range of experimental and ethnopoetic examples. Between the two of us we set out to construct an assemblage of writings (and imagings) that would map (very partially) some 200 years of changes in the way that books are made and thought of – what the idea-of-the-book might mean across that stretch of time down to the present. It was in line with my own earlier work – and that of many others – that we attempted to bring the very distant and the very present into the same field. And we wanted at the same time to expose the material bases (ink & paper, manufacture & dissemination) of those ends to which the work of Mallarmé and others had led us.

A book for me is a big or little structure (a big structure in this instance) made of words. (William Carlos Williams, in the statement that I’m here distorting, uses the word “machine” rather than “structure” – a word echoed by McCaffery and Nichol in the essay that I mentioned before; but Williams of course is defining a poem rather than a book.) In line with this, as our book-of-the-book, we paid particular attention to how the book was divided, how the individual works were arranged and related (both within and between sections), and even how the individual sections were titled. The physical appearance of the book – no small matter in an undertaking of this sort – was largely the work of Steven Clay and his designer-printer Philip Gallo. This also involved a wide range of illustrations, including a color foldout of La prose du transsibérien, the pioneering artist’s book by Blaise Cendrars and Sonia Delaunay, and a facsimile of a complete visual book (O!) by Jess [Collins] that I had published many years before under my own Hawk’s Well Press imprint.

To conclude, then, is to say that here as elsewhere there is no conclusion. “Of the making of books there is no end,” as the old scriptural saw once put it (while reifying a single book as the unalterable word-of-god), and Mallarmé in his modernist détournement: “Everything in the world exists in order to be turned into a book.” It is my sense – at least in our common work as poets – that the movement, the dialectic (to use a once fashionable word) is between book and voice, between the poets (present) in their speaking & the poets (absent) in their writing. That is to say, we are (up to & past our limits) full & sentient beings, & free, as Rimbaud once told us, to possess truth in one soul & one body. For myself [as for many others here present] the return to the book is the step now needed to make the work complete.

Jerome Rothenberg

Paris/London 1997

Encinitas 1999

Both The Book, Spiritual Instrument and A Book of the Book continue to be available through Granary Books.